Lifting the Barriers

to Refueling

As the world gets back on track, many people in Germany and other countries take the train, especially on the commute to work and in metropolitan areas. One of the advantages is resource-saving, environmentally friendly mobility. The propulsion systems have an important part to play in this.

04/2023

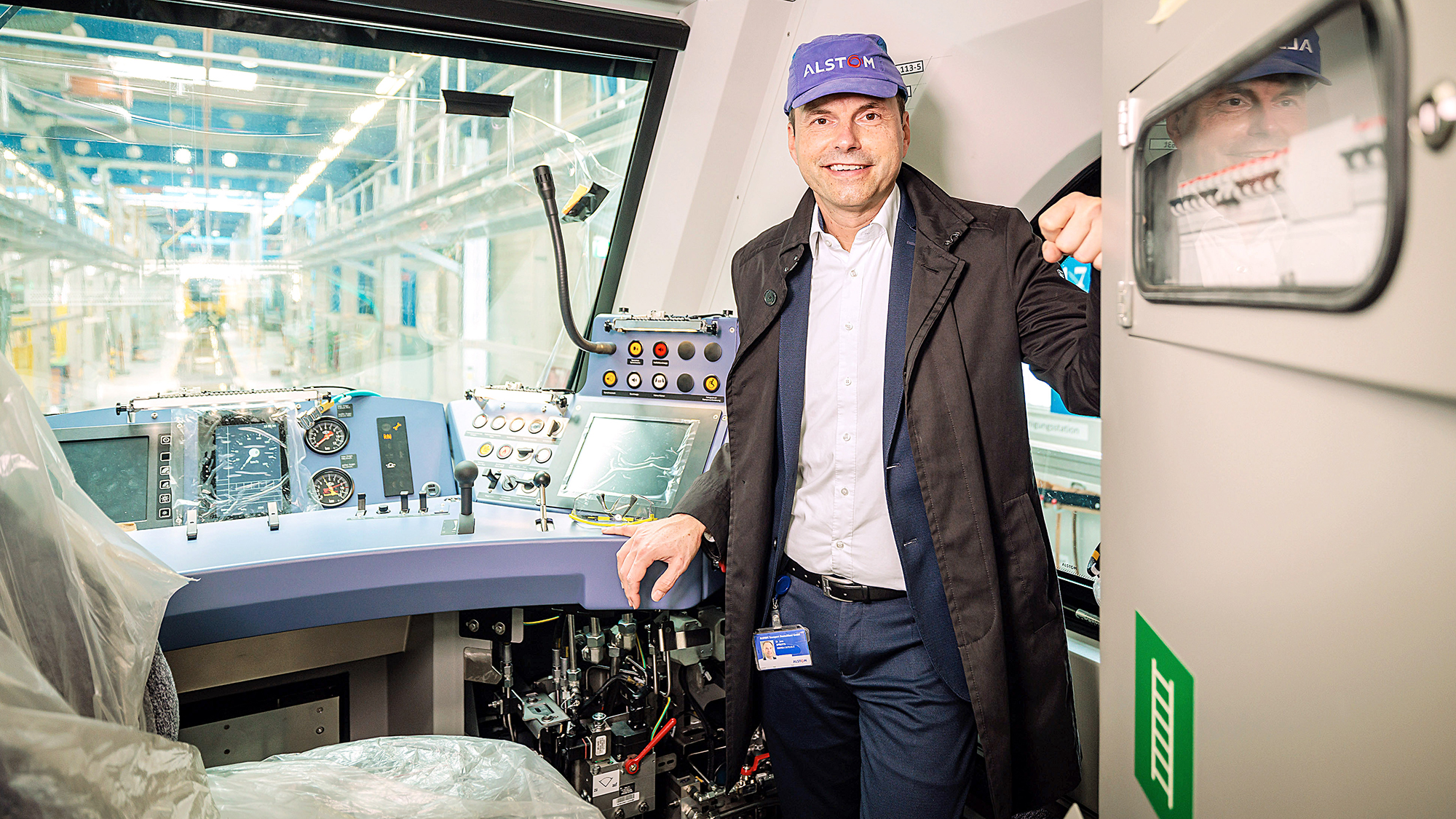

When it comes to future mobility, Jens Sprotte is fully committed to protecting the climate and conserving resources. A man fizzing with energy, Sprotte is the senior manager responsible for the hydrogen-powered Coradia iLint local transport train at the German subsidiary of the French train manufacturer Alstom. If the authorities let the Vice President for Marketing & Strategy have his way, environmentally friendly hydrogen-powered trains could play an important role even sooner. This would be particularly useful in regional public transport, which is characterized by relatively short distances and frequent stops, and where there are many lines that at present can only be operated with diesel locomotives due to the lack of overhead electric lines. The Alstom Group is already showing how a different track is possible in the northern German state of Lower Saxony, where the Coradia iLint runs on a regular service in the North Sea coastal region around Cuxhaven. In summer 2023 the train will also be trialled in Canada, taking passengers along the St. Lawrence River on the Charlevoix Railway. The green hydrogen will be supplied by a Harnois Énergies plant in Quebec City. With the results of this project, Alstom aims to be better able to assess the development of hydrogen technology in the North American market.

Alstom was the first manufacturer to establish the new system with fuel cells from Canada in regular operation. These cells generate electrical energy from hydrogen and oxygen, and the current to drive the train is stored in what are known as traction batteries. The energy generated during braking also flows directly into the batteries for storage. This reduces hydrogen consumption and increases the range.

Vita Jens Sprotte

A world record to boot

For hydrogen trains to make their way onto many more routes, Sprotte needs a lot more attention. He’s getting involved in this with sporting zest, and even organized a world record. He reserved a special slot for his Coradia iLint on the very busy Deutsche Bahn rail network, invited TV crews and newspaper editors to stations in every German state along the route, and sent them on the hydrogen-powered train from the far north to the southern border.

Sprotte originally expected his train to cover at least 1,000 kilometers on just one tank of fuel. The estimate was deliberately cautious, and in the end there was enough left to go much further. The journey ended just before the two onboard tanks were completely empty—after 1,175 kilometers and a consumption of 250 kilograms of hydrogen. That works out to 21.3 kilograms of hydrogen per 100 kilometers of track.

“Our iLint is so economical that it only needs to be refueled every two days in typical regional operation,” boasts Sprotte. But there’s still one incredibly frustrating catch. After the world record trip, the Coradia iLint was unable to return home under its own power. The shiny newcomer had to be coupled to another locomotive. But why? “Because there are hardly any suitable hydrogen refueling stations for trains on the line,” says Sprotte. That has to change, and it’s now becoming clear that manufacturers like Alstom will step in for themselves. “It’s no longer enough for us to put a train on the rails for our customers. When running them on hydrogen, we also have to supply them with the infrastructure and operate it. And that begins with the hydrogen filling stations.”

How Alstom is shaping the future on rails

Hydrogen from the region—for everyone

The infrastructure problem is by no means unique to Alstom. When using hydrogen, people all too often think in terms of their own industry instead of global systems. Logistics, filling stations and efficient use through networks are still in their infancy and have been for years. Admittedly, different users have different applications. “But the hydrogen is always the same. And it has to be available to anyone who wants it, directly where it’s needed. That’s essential in order to leverage synergies and achieve economies of scale,” says Christian Dittmer-Peters. As a partner at the management consultancy Porsche Consulting, he is helping Alstom with its environmentally friendly rail campaign. He is committed to building a “multi-user hydrogen ecosystem.”

On the factory tracks of Alstom Transport Deutschland GmbH in Salzgitter in northern Germany, the new hydrogen trains roll out of the long production halls. Since the end of August 2022, these trains have been gradually replacing the diesel-powered vehicles of the Lower Saxony state public transport authority (LNVG) on scheduled services on the local transport network between Cuxhaven, Bremerhaven, Bremervörde and Buxtehude. The fleet for LNVG will comprise a total of 14 Coradia iLint trains. In Bremervörde, Linde GmbH, the world market leader for industrial gases, built a hydrogen filling station for the trains. The best thing is that the gas comes as a waste product from a chemical plant in the town of Stade, only 30 kilometers away. If it were not used as energy in the trains, it would be disposed of.

The operator—the local transport authority—is extremely satisfied: “By using the hydrogen trains on regular services, in the past few months we have proven that this innovative form of propulsion is in no way inferior to diesel. Quite the opposite,” says LNVG Managing Director Carmen Schwabl. “With the hydrogen project, we’ve given impetus to the development of hydrogen trains in Germany and in order to do even more for the climate, we will no longer buy diesel vehicles.”

And Dr. Mathias Kranz, Linde’s Managing Director of On-site and Bulk Business in Germany, is excited about a new area of business: “At Linde, we’ve been committed to spreading sustainable hydrogen technologies for more than 30 years. By establishing the world’s first hydrogen filling station for trains in Bremervörde, we have opened up a new mobility sector.” The network in the north of Germany is the world’s first scheduled passenger service with hydrogen trains.

“Hydrogen deserves a more motivated approach”

Frankfurt on the same track

Another network, the Rhine-Main transport association (RMV) began operating 27 hydrogen trains in December 2022. They will take passengers from the banking metropolis of Frankfurt am Main to Brandoberndorf in the Taunus region, a town with a population of 2,000. The necessary hydrogen filling station was built in the Frankfurt-Höchst industrial park by Infraserv Höchst, the company that operates the industrial park. RMV Managing Director Prof. Knut Ringat points out proudly that this innovation in the Rhine-Main region is “the largest hydrogen train fleet in the world.” The RMV trains are not only as quiet as electrically powered vehicles, but they also only emit water vapor during operation. This means they save around 19,000 tons of CO2 each year. The hydrogen is produced in the nearby industrial park—also as a waste product from chemical processes. Ringat also cites public mobility without pollution as a goal: “In order to achieve this, we will demand environmentally friendly propulsion systems in all our invitations to tender from 2030,” promises the head of the transport association.

Technologically and also in terms of production processes, the switch to hydrogen has long been part of everyday life for manufacturer Alstom. “The essential drive components were all fully developed and available on the market,” says Alstom manager Sprotte. What’s much more complicated is something that the customer expects to have from the day the trains are delivered: “As a manufacturer, we must provide our customers with an entire ecosystem of the necessary hydrogen infrastructure so that they can be sure they are buying a high-performance, long-lasting means of transport,” says Sprotte. Since the project began, he has had visitors from 35 countries keen to find out more. Other projects in northern Italy, France and the Netherlands are about to start.

Combining the energy and transport sectors

Alstom’s task now is to clear external hurdles out of the way. Sprotte explains this using the Bremervörde project as an example: “The location is geographically favorable, almost in the middle of the regional transport network. If they were allowed to, Alstom and Linde could jointly supply several surrounding communities with ready-made hydrogen, for example for municipal commercial vehicles. But they can’t, and that’s because public funding for the project was only granted on the express condition that the filling station be used exclusively for rail transport.” This was met with incomprehension by the partners involved.

Sprotte says he is committed to getting policymakers to move away from a “transport only” or “energy only” mindset. An energy and transport revolution will only succeed if there is joined-up thinking, in other words, if the hydrogen and transport strategies in Germany are linked. From an economically motivated point of view, the filling station would be much more efficient if it served more than just trains that come by every day or two to refuel, and could instead be used by multiple transportation services. There is plenty of demand—in addition to the fleets operated by local authorities, potential beneficiaries might include scheduled bus services, freight forwarders, large agricultural operations or parcel and courier services.

The train manufacturer Alstom is convinced that hydrogen propulsion has a great future, although experts are aware that in rail transport, nothing tops the efficiency of electricity from an overhead line. “But there are important, very plausible arguments for hydrogen in many places,” says Sprotte: “The infrastructure for electrification is very expensive and is barely worthwhile for regional transport in rural areas.” Electrifying a single-track line costs 1.4 to 3.6 million euros per kilometer, depending on the topography—whether flatlands or hills. These figures were published by the German Federal Ministryof Transport in 2021 according to calculations by DB Netz AG, the Deutsche Bahn subsidiary responsible for rail infrastructure.

Hydrogen has other advantages, too. That’s because ideally, the gas is available as a waste product. When this is not the case, it is possible to use technologies such as wind power, which is sometimes generated in excess and can be converted into hydrogen. This way, costly wind turbines would no longer have to be shut down at times when the demand for electricity is met and there are no customers for the energy.

In Germany, many regional trains currently on the lines were purchased during a boom shortly after the turn of the millennium. They have now been in service for two decades and are about halfway through their life cycle. This includes many of the more than 1,000 LINT diesel trains from Alstom currently operating in Germany’s regional transport system. Their propulsion systems, as well as those of many shunting locomotives, could, according to Sprotte, be converted from mineral oil to hydrogen for a “reasonable outlay”. The main thing is to remove the barriers to refueling.

The train in figures