What Makes a Strong

Crisis Manager

Crises tend to hit people and organizations unprepared. Strong personalities are then needed, who can see the big picture and act calmly. What exactly are the qualities of outstanding crisis managers?

09/2020

Problems keep piling up and the situation is spiraling out of control. Even individuals with strong nerves can lose their bearings and begin to panic. The clock is ticking relentlessly, and time is running out to avert a yet greater disaster. It is a crisis—which is going from bad to worse. Whether in the form of an oil spill, earthquake, famine, war, stock market crash, or pandemic, a disaster or crisis can hit companies, individuals, or entire societies, bringing suffering and death. It is not for nothing that the literature on how to manage crises fills any number of shelves.

The Covid-19 pandemic has once again revealed the need for leaders who can rapidly grasp the big picture. Who can keep their cool and improvise under pressure. Who surround themselves with capable personnel and make far-reaching decisions in very short periods of time. Now is the hour for those who are willing to push the limits, and who are skilled at handling crises. We present five examples of extraordinary individuals who faced economic, social, or political crises—and had the qualities and abilities needed to deal with them.

The Organizer: Florence Nightingale

Nursing and Hygiene Pioneer in the Crimean War

Explosives, steamships, underwater mines—the Crimean War from 1853 to 1856 is considered one of the first armed clashes in history to be waged by industrial means, and a precursor to the brutal battles of attrition in the First World War. It was fought between Russia and an alliance consisting of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain, and Sardinia-Piedmont.

While modern weaponry played a role in the high number of deaths among the allies, so too did an anachronistic medical system. Florence Nightingale, a British nurse, was confronted with the horrendous conditions in military hospitals when she and thirty-eight other nurses traveled to Turkey in 1854. The hospitals there had to handle not only the wounded but also the sick, with three or four thousand soldiers needing care at the same time due to a cholera epidemic. A humanitarian crisis was underway among the troops of the empire. Despite a number of conflicts with physicians and other nurses over responsibilities, Nightingale succeeded in introducing crucial improvements and lowering the mortality rate among soldiers. She was less involved in the everyday direct treatment of patients than in having hospitals reconstructed in accordance with modern standards of care at the time. She bypassed the army’s bureaucratic procurement procedures and used donations solicited via The Times in London to purchase beds, shirts, drinking cups, and socks. She had washing facilities installed, issued lemon juice to prevent scurvy, and added vegetables to meal plans.

With courage, assertiveness, and organizational skills, Florence Nightingale showed herself to be an extraordinary crisis manager. Although she herself returned chronically ill from the Crimean War in 1856, she applied much of the knowledge gained in Turkey to the public healthcare system in Britain. Among other things, she wrote popular guides for care personnel, founded a school for nurses, and used social statistics to support her positions.

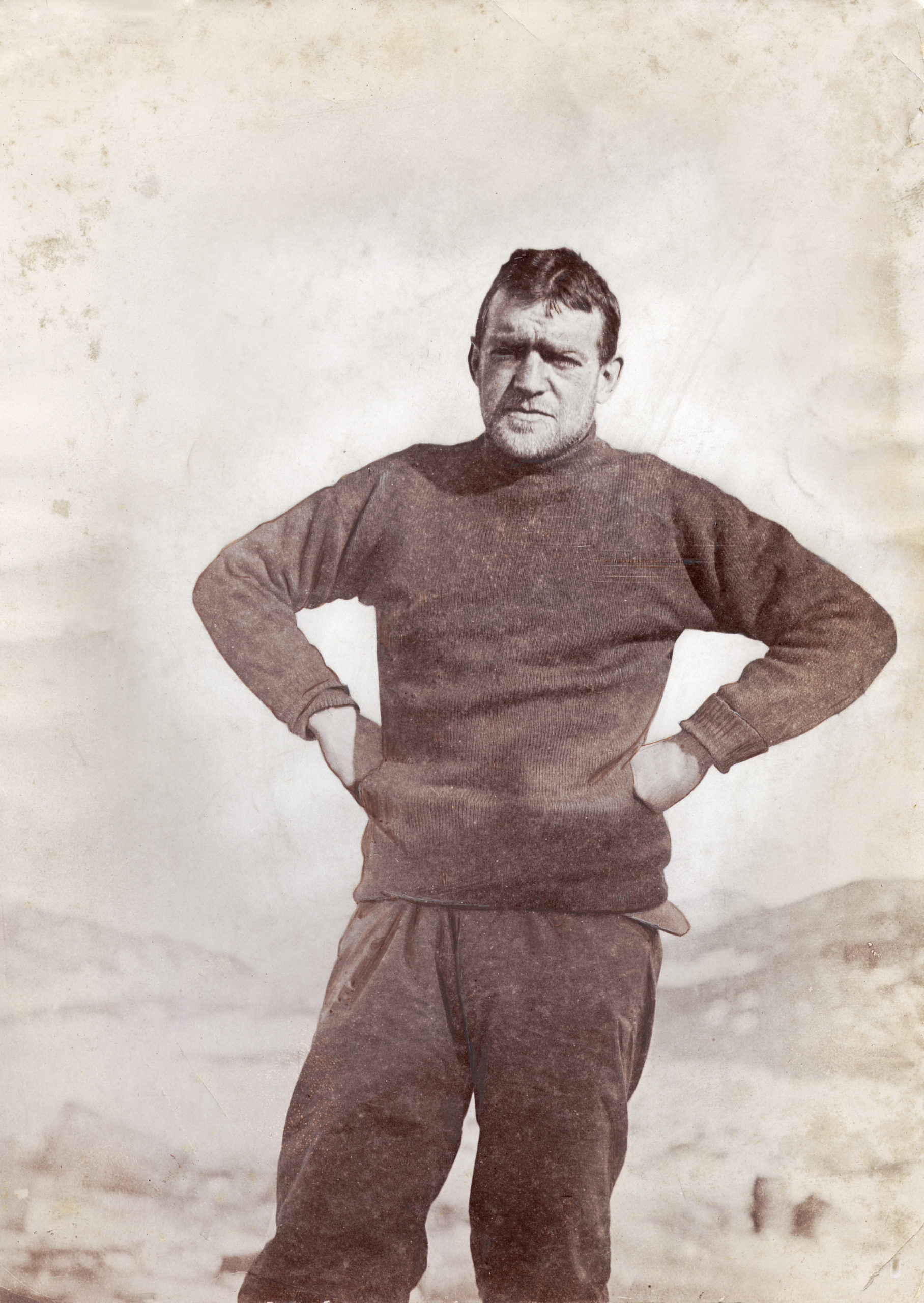

The Lifesaver: Ernest Shackleton

Polar Explorer and Antarctica Expedition Leader

On October 27, 1915, it was clear that the expedition had failed. The crew had to leave the ship. For a good ten months, the “Endurance”—a three-mast sailing vessel around forty-four meters in length with an auxiliary steam engine—had been trapped in the ice. And now her robust hull was being crushed by pack ice in the Weddell Sea, despite tropical-wood frame elements more than twenty-eight centimeters thick. The ship was at risk of sinking rapidly. The crew of the British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition evacuated onto an ice floe. Now they had to face their fate alone and unprotected in the hostile world of Antarctica. But they were fortunate in having Shackleton as their capable and indefatigable leader.

More than a year earlier, on August 8, 1914, Shackleton and his twenty-six-member crew had set off in the 350-ton wooden ship from Plymouth, England. Their ambitious aim was to be the first to cross the continent of Antarctica. From coast to coast, through the geographical south pole.

Shackleton had carefully selected his crew for the hazardous expedition from more than 5,000 applicants. Their number included experienced sailors and accomplished scientists, plus a photographer and a painter charged with making a visual record of the endeavor. Shackleton himself had trained with the British merchant marine and had already proved his skills in previous expeditions to Antarctica.

But in addition to experience and skill, it was Shackleton’s knowledge of human nature that helped bring out the right characters and abilities of his team members. On the arduous voyage to Antarctica Shackleton had already boosted their morale with the help of physical exercise, dog races, and games. And even after the wreck of the Endurance, as the men set up their tents under icy conditions, he succeeded in fostering a sense of solidarity and unifying the crew around the new goal of sheer survival and rescue.

When the weather let up after a number of weeks, he led the group in three lifeboats to Elephant Island, which was uninhabited. He then left most of the crew there and set off with five men in one of the boats to get help from the whaling stations on South Georgia Island—a good 1,500 kilometers across the open icy sea. He took his best navigator and also a very motivated volunteer, plus a third man whose sense of humor could buoy the spirits of the little group. The other two men were on the pessimistic side, but Shackleton did not want to leave them behind because he feared they might undermine the larger group’s morale. After two weeks at sea the boat reached South Georgia Island and a ship was sent to rescue the crew members waiting on Elephant Island.

“Not a life lost and we have been through Hell,” wrote Shackleton to his wife Emily after the rescue. His determination and leadership, drawing on values like loyalty and camaraderie, are seen as the key to this achievement by his team.

The Doer: Helmut Schmidt

Interior Minister in Hamburg During the 1962 Flood

A hard-hitting German chancellor in the battle against Red Army Faction terrorists. A high-profile publisher of a weekly magazine. A sought-after expert on world affairs rarely seen without a menthol cigarette. Over the course of his life, Helmut Schmidt played many roles on the sociopolitical stage. None was as perfectly tailored for this heavy smoker as the one that expedited his already promising career. And the one he embellished upon in subsequent decades in line with all the maxims of self-marketing. Namely, that of Hamburg’s crisis-vetted “senator of the police department” during the floods that overwhelmed the Hanseatic city in the spring of 1962. The office is comparable with that of an interior minister on the federal level, and Schmidt had assumed it in the northern German city-state in 1961 after relinquishing the seat he had held in the federal parliament since 1953.

In February 1962, the Vincinette low-pressure system sent masses of water rushing from the North Sea into the German Bight. In the night of February 16-17, several decrepit levees in Hamburg broke down. Walls of ice-cold water flooded into the district of Wilhelmsburg near the port. Many people drowned in their homes. Schmidt met with the crisis management team at police headquarters in the early hours of the morning. Gas lanterns were their source of light because power was out in much of the city. Rescue operations were already underway, and helicopters were needed. Drawing on his contacts as a former member of the federal parliament, Schmidt mobilized additional forces from the German military and NATO. His commanding presence helped to accelerate the requisite decision-making processes.

“I didn’t care about legalities,” is one of the famous quotes by Schmidt—nicknamed “Schmidt Schnauze” (roughly, “Big-mouth Schmidt”)—about the dramatic events of the crisis. That might have been true in a subjective sense, but objectively speaking, it had already been legal for several years in Germany to deploy the military in crises. Without a doubt, however, Schmidt succeeded in gathering all available resources and rescuing many people from inundated areas that were quickly freezing over. The flood caused millions of marks’ worth of damage and claimed 340 lives. But how many more lives might have been lost without Helmut Schmidt to manage the crisis?

The Streamliner: Ken Allen

CEO of DHL Express in the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis

“A crisis is the best time for the best to play at their best,” said Ken Allen in 2010. He knew what he was talking about. He had been CEO of the DHL Express logistics provider when the recession struck in 2007-2008. He gave his best and saved the U.S. division of DHL Express from bankruptcy. And because this British manager’s “appetite for crises” was evidently not yet stilled, he ordered dessert. After his promotion to CEO of the ailing parent company in 2009, he set about revitalizing it in record time. The financial crisis had relentlessly exposed the weaknesses of DHL Express. Its costs were too high, and its revenues were too low. Although its real strength lay in transnational logistics, the company was incurring domestic losses in the UK and in France. Moreover, its administrative structures were obsolete.

Allen’s operating principle is “less is more.” He is viewed as a master in setting priorities, focusing on essentials, and putting plans resolutely into practice. At the same time, he possesses a fine instinct for identifying future-oriented projects worthy of ongoing investment. In an article for the Harvard Business Manager in 2019, Allen advised business leaders facing crises to ask themselves not only what they should be doing, but also and especially the key question of what they should no longer be doing.

With this as a guide, Allen set to work at DHL in 2009. He made the board smaller and reduced the number of regional administrative bodies. He outsourced less profitable business sectors to partners. He based the size of the company’s workforce on the extent of its recovery from the crisis, while at the same time having employees trained for the more profitable field of international business. He held onto strategically important innovation-based projects. This course of action proved itself in the years that followed. The Group’s costs dropped by 480 million euros by the end of 2009, and DHL was back on track. Ken Allen has been viewed as one of the world’s top crisis managers ever since.

The Fighter: Vanessa Nakate

Climate and Anti-Racism Activist

Ugandan native Vanessa Nakate is not a crisis manager in the classical sense. But the crises that this twenty-three-year-old tackles are anything but conventional. Nakate is a climate activist and also a fighter for a world without racism. For both of these issues she has a perspective that is foreign to most people in the West: she looks at the bubble of the white industrial world from outside.

Inspired by Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, Nakate began striking for climate protection in January 2019 by standing in front of the Ugandan parliament in the capital city of Kampala. She was still a student, but had seen that heat waves, droughts, and storms had been posing ever greater threats to the conditions for life in her homeland. She was also aware of a crisis within this crisis. She realized that Africa was not sufficiently included in public perception of the climate movement, that the Fridays for Future movement revolved primarily around the fears and concerns of western industrial nations, and that young people in Africa lacked knowledge about climate change—and therefore also about how to formulate political demands. While her fellow students stayed home due to fear of reprisals, Nakate carried on her strike with courage and determination. She made posters and banners with the help of her siblings, and demonstrated for a long time alone.

In January 2020 Nakate traveled to the World Economic Forum in Davos, where she met Thunberg and other activists like Luisa Neubauer from Germany. A photo was taken of the group, but Nakate was cropped out by the Associated Press news agency. Nakate used social media to publicize the incident. “Africa is the least emitter of carbons, but we are the most affected by the climate crisis,” she said in a video on Twitter. “You erasing our voices won’t change anything. You erasing our stories won’t change anything.” Her tweets and videos on the subject have been shared hundreds of thousands of times. AP publically admitted their mistake and replaced the photo. Vanessa Nakate’s resolute action has attracted a great deal of attention—for her and thereby also for her fight against a twofold crisis.